Clean Air Advocacy Ireland’s Submission to the Department of Climate, Energy and the Environment for its Public Consultation on Ireland’s Clean Air Strategy

Clean Air Advocacy Ireland welcomes the Department’s recognition of the importance of Clean Air. It is encouraging to read that the Government understands that clean air is essential for our quality of life, and we welcome the invitation to contribute to the development of a National Clean Air Strategy through this public consultation.

The Air We Breathe

Air quality, both indoors and outside, plays a pivotal role in the health and well-being of individuals. While outdoor air quality has received significant—if not all—attention in the Government’s Clean Air Strategy, the importance of indoor air quality (IAQ) remains under-acknowledged despite its profound implications for public health. This is especially so, as most people spend 90% of their time indoors. We must consider and include our indoor environments as part of our environment when developing a National Clean Air Strategy.

The Government’s current focus includes the regulation of solid fuel use and its impact on public health, particularly the mental health effects of particulate matter (PM2.5).[1] Despite these efforts, the strategy must expand to include IAQ in public and private indoor spaces. Studies have shown that poor IAQ significantly affects health, contributing to respiratory diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, as well as mental health difficulties.[2]

Health Impacts of Poor Indoor Air Quality

PM2.5 an NO2

Research has established a strong correlation between poor IAQ and adverse health outcomes. For instance, exposure to PM2.5 in indoor environments has been linked to numerous health conditions, including asthma, rhinitis, bronchitis, lung cancer, and even mental health difficulties such as anxiety and depression.[3] Air pollution exposure during pregnancy is a critical risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes and impaired child development. Fine particulate matter PM2.5 and NO2 can cross the placenta, leading to issues like low birth weight, preterm birth, stillbirth, and altered foetal brain/lung development. These pollutants are associated with long-term risks such as childhood asthma, reduced cognitive performance, and increased risk of neurodevelopmental difficulties.[4] Further compounding the issue, a study on the association between air pollution and cognitive decline revealed that PM2.5 and NO2 significantly impair cognitive function, especially in individuals over the age of 40. The study concluded that these pollutants are associated with diminished executive function and verbal fluency, suggesting long-term impacts on human cognition.[5]

An Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) study from 2013 underlined the urgent need for policy interventions to mitigate the harmful effects of indoor air pollution, particularly among vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly.[6]

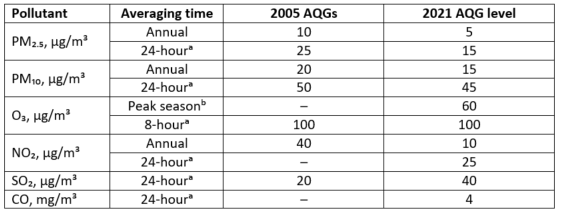

The World Health Organisation (WHO) have developed air quality guidelines which are a set of evidence-based recommendations of limit values for specific air pollutants developed to help countries achieve air quality that protects public health. The first release of the guidelines was in 1987. Since then, several updated versions have been released, and the latest global version was published in 2021.[7]

Recommended 2021 AQG levels compared to 2005 air quality guidelines.

WHO Air Quality Guidelines

The WHO air quality guidelines should be used as an evidence-informed reference tool to help in developing a National Clean Air Strategy for Ireland, and to set legally binding standards and goals for air quality monitoring and management at national and local level. Many of these 6 listed pollutants are generated indoors from burning fossil fuels or cooking and can also filter into buildings from outdoors through cracks in walls, windows and chimneys.

The HSA Code of Practice for Indoor Air Quality

The Health and Safety Authority's Code of Practice for Indoor Air Quality provides detailed guidelines for maintaining appropriate Indoor Air Quality in workplaces.[8] The Code emphasizes the necessity for clean air in indoor environments, highlighting that employers are responsible for ensuring sufficient ventilation, either through natural or mechanical means. Employees have the right to request workplace risk assessments that include considerations of ventilation.[9] According to the Safety, Health and Welfare at Work (General Application) Regulations 2007, recently amended by S.I. 255 of 2023, it is a legal requirement for employers to provide sufficient fresh air in enclosed workplaces, either through natural, mechanical, or combined ventilation strategies.[10]

We submit that the existing guidelines under the HSA’s Code of Practice for Indoor Air Quality are excellent and it is particularly positive that the guidelines have been given a statutory footing. However, awareness remains an issue. Due to there being such little awareness around these guidelines amongst employers, employees and members of the public more generally; workers, children, patients and carers, who inhabit workplace environments like schools and healthcare facilities are not aware that they can make formal complaints to the Health and Safety Authority regarding poor IAQ. Increased awareness of the HSA’s Code of Practice for Indoor Air Quality amongst school and hospital administrators as well as other employers combined with greater enforcement by the HSA, would go a long way towards improving air quality for the most vulnerable in our society.

Indoor Air Pollution and Children

Indoor air quality is a critical issue for the 1 in 5 children in Ireland affected by asthma.[11] Poorly ventilated homes, dampness, mould, tobacco smoke, and cleaning chemicals often make indoor air up to five times more polluted than outdoor air, triggering uncomfortable symptoms and increasing hospitalizations.[12]

Exposure to PM2.5 in indoor environments has been linked to numerous health conditions, including asthma, rhinitis, bronchitis, lung cancer, and even mental health difficulties such as anxiety and depression.[13]

A 2016 study (reaffirmed in February 2024) by the American Academy of Paediatrics demonstrated that portable, high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) purifiers reduce particles in the air by around 25–50% and reduce asthma symptoms and attacks.[14]

CO2 monitoring of indoor environments is a useful proxy indicator of how well-ventilated a room is[15].

We submit that continuous livestreamed Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) Monitoring and HEPA filters should be required by regulation and distributed throughout all classrooms and hospitals. Continuous IAQ monitoring would enable students and staff, patients and parents to view the air quality of a room and to allow for steps to be taken to improve the air quality in the indoor environment. Whether that be opening windows, installing extra HEPA filters, or identifying a point source for poor air quality. Transparency in accessing such data is essential for building trust and community in tackling the issue.[16]

We propose that HEPA filters should be prescribed free of charge to young asthmatic patients to take home to protect their health by reducing the number of asthmatic flare-ups, in turn reducing numbers of hospital emergency departments attendants requiring treatment.

Bio-Aerosols

We cannot discuss the public health impacts of poor IAQ without discussing the mounting scientific research and evidence gathered over the last six years of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

While the World Health Organization declared in May 2023 that SARS-CoV-2 was no longer a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, COVID-19, as it is commonly known, is still considered to be a pandemic as it continues to mutate and circulate across multiple jurisdictions around the globe.[17]

The biggest discovery from this pandemic was that SARS-CoV-2 and most colds, influenza, and other respiratory illnesses are spread via bio-aerosols that hang in the air like smoke, and are not only droplet-spread.[18] This is true also for Measles which is now making a global resurgence due to a decrease in vaccination coverage.[19]

Thanks to world renowned aerosol scientists spearheaded by Professor Lidia Morawska, Professor Yuguo Li and Dr. Linsey Marr, we now know that many pathogens are in fact spread through the air we breathe via aerosols smaller than 100 microns. These aerosols can linger for hours in an empty room, especially if there is poor ventilation in place.[20]

The Public Health Impact of Airborne Viruses

Six years on from the arrival of SARS-CoV-2, we have learned a lot more about how viruses can trigger post-viral sequelae.[21]

Research that emerged during the pandemic confirms a strong, likely causative link between the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Almost all people with MS have been infected with EBV, and infection increases the risk of developing MS.[22]

It is well established that shingles is an infection that is caused by the chickenpox (varicella zoster) virus[23]. Recent studies now show a strong potential link between herpes zoster (shingles) and a higher risk of dementia, while vaccination with the shingles vaccine is associated with a 20% lower risk of developing dementia over seven years. The herpes zoster virus may cause neuroinflammation or vascular damage, accelerating cognitive decline.[24]

It is now well understood that SARS-CoV-2 can cause long-term health issues known as Long COVID, a chronic condition which is best understood as a collection of overlapping symptoms rather than a single post-viral condition. The main symptom patterns associated with Long COVID identified to date include: neurologic, respiratory, olfactory and/or gustatory, cardiopulmonary, and fatigue[25].

There is widespread consensus amongst scientists and cardiovascular specialists that SARS-CoV-2 infections cause significant accelerated vascular ageing.[26]

Unlike prior pandemics, the current era offers advanced technologies and analytic tools to help us better understand how some viruses can leave lasting public health impacts. As we continue to learn more, it is an opportunity to improve our indoor environments to prevent the spread of airborne viruses to not only reduce their acute effects, but to tackle the long-term chronic health impacts as well.

SARS-CoV-2 and Children

In the early days of the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 was considered to be of lower risk to children without scientific support to back this claim. As a result, schools reopened and classroom environments gradually returned to “pre-pandemic normalcy”, i.e. there has been less emphasis on classroom ventilation and use of CO2 monitors to assess ventilation, or use of HEPA filters in classrooms to filter airborne pathogens. In addition, Covid vaccines are not easily available to the majority of children—children between 6 months and 12 yrs of age can only access vaccines through public health nurse appointments and are not routine vaccines.

Extensive scientific research now shows that children are in fact vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infections, with effects lasting beyond the acute phase of infection. A recent Centre for Disease Control and Prevention study suggests that school-aged children in the US diagnosed as having Long COVID are at 2.5 times the risk of related chronic absenteeism compared with those without the condition. The study, published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, also found double the prevalence of memory impairment, problems concentrating, and learning difficulties in this group. The researchers used data from the 2022 and 2023 US National Health Interview Surveys to evaluate functional limitations and illness-related chronic absenteeism in a nationally representative sample of 11,057 children aged 5 to 17 years comparing those who had Long Covid with those who hadn't.[27]

There is also a chronic absenteeism crisis in Irish schools as the number of children missing 20+ days/year has more than doubled since the onset of the COVID pandemic, affecting 1 in 5 students.[28] While there is no reliable data on Long COVID rates amongst children in Ireland,[29] the pattern of school absenteeism due to illness is also being observed here.

In 2023-24, there were 94,501 students who lost 20-plus days at primary level, representing 22.1% of the student population. The percentage of students absent for 20 days or more at primary level is 8.41 points above the long run average (2003-2023) of 13.64%.

At post-primary level, 67,612 students lost 20 or more days, representing 21.2% of the student population.

At post-primary level, the percentage of students absent for 20-days or more is 4.48 points above the long run average of 16.7%. Both figures remain well above the pre-pandemic averages of 11.43% and 16.19% for primary and post-primary respectively.[30].

In 2023–24, the category of illness accounted for the highest number of absences in primary schools for the third consecutive year, representing 39.9% of days lost. In post-primary schools, “unexplained” absences accounted for the largest share of absences at 52.7%, also for the third consecutive year.[31]

We know now that many pathogens are spread via aerosols, and that some of the post-viral sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infections in children include cardiovascular disease,[32] immune dysregulation, anxiety, memory and mental health issues.[33] Such a dramatic increase in school absence rates amongst school children in Ireland underscores the urgency of implementing comprehensive IAQ measures to prevent further damage being caused to children from airborne pathogens like SARS-CoV-2.

We submit that continuous livestreamed Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) Monitoring and HEPA filters should be required by regulation and distributed throughout all classrooms. Continuous IAQ monitoring would enable students, staff and parents to view the air quality of a classroom and to allow for steps to be taken to improve the air quality in the indoor environment. Whether that be opening windows, installing extra HEPA filters, or identifying a point source for poor air quality.

Indoor Air Quality for Accessibility

Following on from the above discussion about how our indoor environments can negatively impact public health by triggering asthma attacks, or causing chronic illnesses, it is also exceedingly important to emphasise that many people who are living with invisible chronic illness, who are immunocompromised, or who share households with immunocompromised individuals are being excluded from full participation in society due to the risk posed by poor IAQ and prevalence of airborne pathogens.[34] People with chronic and often invisible health conditions are rarely considered in organisational diversity, equality and inclusion (DEI) policies. They may be incorporated into umbrella disability policies but many do not self-identify as living with a disability. We must expand our thinking on DEI policies to include safe indoor air so that we make our spaces accessible and inclusive for all.[35]

Climate Change and Preparing for Future Pandemics

The SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic should have been a wakeup call on how to better prepare ourselves for future pandemics. Unfortunately, many of the lessons that should have been learned from SARS-CoV-2 have still not been learned or widely adopted in public policy.

Ireland was not prepared with the appropriate PPE for frontline workers or members of the public when SARS-CoV-2 first arrived on our shores. We now know that cloth masks and surgical masks are not very effective at preventing the transmission of airborne viruses and that FFP3 or FFP2 respirators are required.

There was widespread disinformation[36] and politicisation of masks[37] during the emergency phase of the Covid Pandemic, with masks becoming a symbol of government control and oppression. Yet early in a pandemic, when drugs and vaccines are unavailable, masks are among the few available protective measures, especially for frontline workers[38].

A recent study published in Nature Scientific Reports warns of a 'creeping catastrophe' as climate change drives a global rise in infectious diseases. The research determined insight from 3,752 health professionals and researchers across 151 countries and is one of the largest Global studies of its kind[39].

This research found that experts around the world consider vector-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue as the most rapidly escalating threats, followed by tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS. The research confirmed they find the three main drivers are:

Climate change, especially rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns, emerged across all regions as a primary driver of disease escalation as it expands mosquito and other vector ranges, increases breeding sites, and accelerates human mobility and displacement.

Socioeconomic inequality, affecting living conditions and access to healthcare.

Antimicrobial resistance, undermining treatments for a wide range of infections worldwide[40].

Ireland may be fortunate to be in the Northern Hemisphere and removed from the harshest consequences of climate change. However, we are not isolated from global patterns of migration driven by populations being displaced from jurisdictions negatively impacted by climate change, politics, tourism, economic trade and from increasing emigration flows from Ireland due to our national housing crisis. We have never been more connected to the rest of the world than we are today[41]. Our increased connectivity to the world is driving local and international air pollution, climate change, and the risk of introducing/spreading new pathogens with pandemic potential.

Ireland’s Clean Air Strategy should recognise our environmental impact on the global south and contribution to driving pandemics through our contribution to climate change.

While this may be beyond the scope of a National Clean Air Strategy, we submit that greater interdepartmental collaboration should exist to deal with the intersection between Climate Change, Domestic Air Pollution, and both Communicable and Non-Communicable Disease.

We propose that to be better prepared for new pandemics, greater efforts should be made now to destigmatise and depoliticise the use of respirators. There was an opportunity at the beginning of the pandemic to upgrade ventilation and improve indoor air quality during the lockdown period. There is still work to be done on upgrading ventilation systems across public buildings, particularly schools to avoid lengthy lockdowns the next time a pandemic arrives on our shores.

Conclusion

The evidence supporting the regulation of IAQ is compelling. From respiratory illnesses to cognitive impairments, poor indoor air quality has far-reaching impacts on public health. Governments must prioritize IAQ in their clean air strategies and ensure that all indoor environments—particularly higher-risk environments such as workplaces, schools, and hospitals—adhere to established standards. By incorporating IAQ into public health policies, the Irish Government can safeguard the health of its citizens and create cleaner, healthier environments for future generations. Clean Air Advocacy Ireland would welcome the opportunity to discuss this submission further.

Sinéad O’Brien

Clean Air Advocacy Ireland

Cong,

Co. Mayo

Email: cleanairadvocacyireland@gmail.com

Website: www.cleanairadvocacyireland.org

[1] ‘Air Quality’, Government of Ireland, (2023). Available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/e3da2-air-quality/?referrer=http://www.gov.ie/cleanair/#health-impacts

[2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2020). Exposure to Pollutants and Health Outcomes. NICE Guidance. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng149/evidence/2-exposure-to-pollutants-and-health-outcomes-pdf-7020943887

[3] Ibid

[4] Korten, Insa et al. “Air pollution during pregnancy and lung development in the child.” Paediatric respiratory reviews vol. 21 (2017): 38-46. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2016.08.008

[5] Thompson, L. et al. (2022). Air Pollution and Cognitive Decline: Meta-Analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 804, 150-162. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S004896972207334

[6] Environmental Protection Agency. (2013). Indoor Air Pollution and Health. EPA Publications. Available at: https://www.epa.ie/publications/research/environment--health/Indoor-Air-Pollution-and-Health.pdf

[7] https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/who-global-air-quality-guidelines

[8] HSA, Code of Practice for Indoor Air Quality (2023), https://www.hsa.ie/eng/publications_and_forms/publications/codes_of_practice/code_of_practice_for_indoor_air_quality/

[9] Health and Safety Authority, (2023).

[10] Health and Safety Authority, (2023).

[11] It is worth noting that Long Covid is now the leading chronic illness in children, surpassing asthma in the United States according to JAMA https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2834486 Without Irish data on Long Covid in this cohort, we don’t know if this is also the case in Ireland.

[12] Asthma Society of Ireland

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2020). Exposure to Pollutants and Health Outcomes. NICE Guidance. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng149/evidence/2-exposure-to-pollutants-and-health-outcomes-pdf-7020943887

[14] Matsui, E. C., Abramson, S. L., Sandel, M. T., Dinakar, C., Irani, A.-M., Kim, J. S., Mahr, T. A., Pistiner, M., Wang, J., Lowry, J. A., Ahdoot, S., Baum, C. R., Bernstein, A. S., Bole, A., Brumberg, H. L., Campbell, C. C., Lanphear, B. P., Pacheco, S. E., Spanier, A. J., & Trasande, L. (2016). Indoor environmental control practices and asthma management. Pediatrics, 138(5). https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/138/5/e20162589/60439/Indoor-Environmental-Control-Practices-and-Asthma?autologincheck=redirected

[15] Ha, W., Zabarsky, T. F., Eckstein, E. C., Alhmidi, H., Jencson, A. L., Cadnum, J. L., & Donskey, C. J. (2022). Use of carbon dioxide measurements to assess ventilation in an acute care hospital. American journal of infection control, 50(2), 229–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2021.11.017

[16] See research on the Boston Public School experience in rolling out IAQ sensors across a school district. A study from researchers at Boston University’s School of Public Health, conducted using data from Boston Public School’s extensive network of air quality sensors, showed classroom air quality is often highly variable within school buildings, and even fluctuates greatly within the same classroom over the course of a year. Yirong Yuan, et al. ‘Estimating air exchange rates in thousands of elementary school classrooms using commercial CO2 sensors and machine learning’, Indoor Environments, Volume 2, Issue 2, 2025, 100083, ISSN 2950-3620, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indenv.2025.100083.

Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2950362025000128

[17] “We cannot talk about COVID in the past tense. It’s still with us, it still causes acute disease and Long COVID, and it still kills… The world might want to forget about COVID-19, but we cannot afford to.” Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director General (2024).

[18] Morawska et. al., ‘Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: The world should face the reality’, Environment International Volume 139, June (2020), 105730, Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016041202031254X

See also: ‘The 60-Year-Old Scientific Screwup That Helped Covid Kill,’ Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/the-teeny-tiny-scientific-screwup-that-helped-covid-kill/

[19] Venkatesan, Priya, Global resurgence in measles, The Lancet Microbe, (January 2026) Volume 0, Issue 0, 101347 Available at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247(26)00002-9/fulltext?rss=yes

[20] Wang CC, Prather KA, Sznitman J, Jimenez JL, Lakdawala SS, Tufekci Z, Marr LC., ‘Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses.’ Science. (2021);373(6558): eabd9149. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9149. PMID: 34446582; PMCID: PMC8721651. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8721651/#:~:text=Virus%2Dladen%20aerosols%20(%3C100,both%20short%20and%20long%20ranges.

[21] Christine M. Miller, Janna K. Moen, Akiko Iwasaki, ‘The lingering shadow of epidemics: post-acute sequelae across history’, Trends in Immunology, Vol. 47, Issue 1, (2026), Pages 9-18, ISSN 1471-4906,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2025.10.010. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471490625002674

[22] EBV is believed to trigger MS through molecular mimicry, where immune cells fighting the virus mistakenly attack myelin, and by triggering B-cells to attack the brain. See,

Farah Wahbeh and Joseph J. Sabatino, ‘Epstein-Barr Virus in Multiple Sclerosis; Past, Present, and Future’, Neurology Journals, (November 2025), 12 (6) e200460 https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000200460

[23] https://www2.hse.ie/conditions/shingles/

[24] Eyting, M., Xie, M., Michalik, F. et al. ‘A natural experiment on the effect of herpes zoster vaccination on dementia’. Nature 641, 438–446 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08800-x Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-08800-x#:~:text=Apart%20from%20this%20large%20difference,than%20the%20existing%20associational%20evidence.

[25] Wang, Bingyi et al., ‘Identifying subtypes of Long COVID: a systematic review’, eClinicalMedicine, Volume 91, 103705 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(25)00639-X/fulltext

[26] Bruno, R. M., et al. (2025). Accelerated vascular ageing after COVID-19 infection: the CARTESIAN study. European Heart Journal 46 (39): 3905-3918. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/46/39/3905/8236450

[27] Ford ND, Simeone RM, Pratt C, et al. Functional Limitations and Illness-Related Absenteeism among School-Aged Children with and without Long COVID, United States, 2022–2023. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2025;31(14):11-19. doi:10.3201/eid3114.251035. Available at: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/31/14/25-1035_article#;

[28] Moya et al. ‘School-level patterns of non-attendance, 2022/23 and 2023/24’, ESRI, (January 2026). Available at: https://www.esri.ie/publications/school-level-patterns-of-non-attendance-2022-23-and-2023-24

[29] The FADA study carried out by the HSE found that 16% of adults reported Long COVID symptoms post infection, but children were unfortunately excluded from this study.

[30] TUSLA Education Support Service, ‘School Attendance Data Primary and Post-Primary Schools And Student Absence Reports Primary and Post-Primary Schools 2023-2024’, (February 2025), Available at: https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/Analysis_of_School_Attendance_Data_2023-24.pdf

[31] IBID

[32] Zhang, B., Thacker, D., Zhou, T. et al. ‘Cardiovascular post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 in children and adolescents: cohort study using electronic health records.’ Nat Commun 16, 3445 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56284-0 Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-56284-0

[33] Boyarchuk O, Volianska L. ‘Autoimmunity and long COVID in children.’ Reumatologia. (2023); 61(6):492-501. doi: 10.5114/reum/176464. Epub 2024 Jan 18. PMID: 38322108; PMCID: PMC10839920. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10839920/

Ortega-Martin E, Richards-Belle A, Newlands F, Shafran R, Stephenson T, Rojas N, et al. ‘Children and young people with persistent post-COVID-19 condition over 24 months: a mixed-methods study.’ BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2025;9:e003634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2025-003634 Available at: https://bmjpaedsopen.bmj.com/content/9/1/e003634

[34] Roberta Savli, ‘Poor indoor air quality: a public health problem,’ European Federation of Allergy and Airway Diseases Patients Association (2017).

[35] See, ‘The Safer Air Project’ in Australia, https://www.saferairproject.com/improving-inclusion

[36] Sule S, DaCosta MC, DeCou E, Gilson C, Wallace K, Goff SL. Communication of COVID-19 misinformation on social media by physicians in the US. JAMA Netw Open2023;6:e2328928. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.28928 pmid:37581886

[37] Thacker PD, The US politicisation of the pandemic: Raul Grijalva on masks, BAME, and covid-19. BMJ2020;370:m3430. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3430 pmid:32900758

[38] MacIntyre et al., ‘The role of masks and respirators in preventing respiratory infections in healthcare and community settings’, BMJ 2025;388:e078573 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ bmj‑2023‑078573 Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/388/bmj-2023-078573.long

[39] Walker, R.J., Kingpriest, P.T., Gong, J. et al. Global perspectives on infectious diseases at risk of escalation and their drivers. Sci Rep 15, 38630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22573-3 Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-22573-3?utm_campaign=oa_20251104&utm_content=10.1038%2Fs41598-025-22573-3&utm_medium=email&utm_source=rct_congratemailt#citeas

[40] Ibid

[41] Over 34.7 million passengers passed through Irish airports in 2017 and the network is expected to deliver around 45 million passengers a year by 2027. See: Global Ireland, Ireland’s Global Footprint to 2025, Government of Ireland. Available at: https://assets.ireland.ie/documents/Irelands_Global_Footprint_to_2025.pdf